Rapamycin and Metabolic Effects: Blood Sugar, Cholesterol, and What to Monitor

Rapamycin and Metabolic Effects: Blood Sugar, Cholesterol, and What to Monitor

The pursuit of human longevity has transitioned from speculative “elixirs” to the rigorous science of geroprotection, with the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway serving as a central hub. While Rapamycin is the most robust pharmacological intervention for extending lifespan in model organisms, its translation to healthy humans is complicated by its powerful metabolic footprint. In clinical settings, Rapamycin acts as a “starvation-mimetic,” yet its chronic use can paradoxically trigger hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia, potentially counteracting its pro-longevity benefits if not meticulously managed. Understanding the nuanced “sweet spot” of low-dose intermittent dosing is critical to capturing the drug’s ability to stimulate autophagy and reduce inflammaging without destabilizing metabolic homeostasis.

How Does Rapamycin Affect Blood Sugar and Insulin Sensitivity?

Rapamycin can induce transient glucose intolerance and insulin resistance by unintentionally inhibiting mTORC2 and upregulating hepatic gluconeogenesis. While acute treatment can prevent nutrient-induced insulin resistance, chronic or high-dose exposure often mimics a “diabetes-like syndrome” characterized by elevated fasting glucose and impaired glucose disposal.

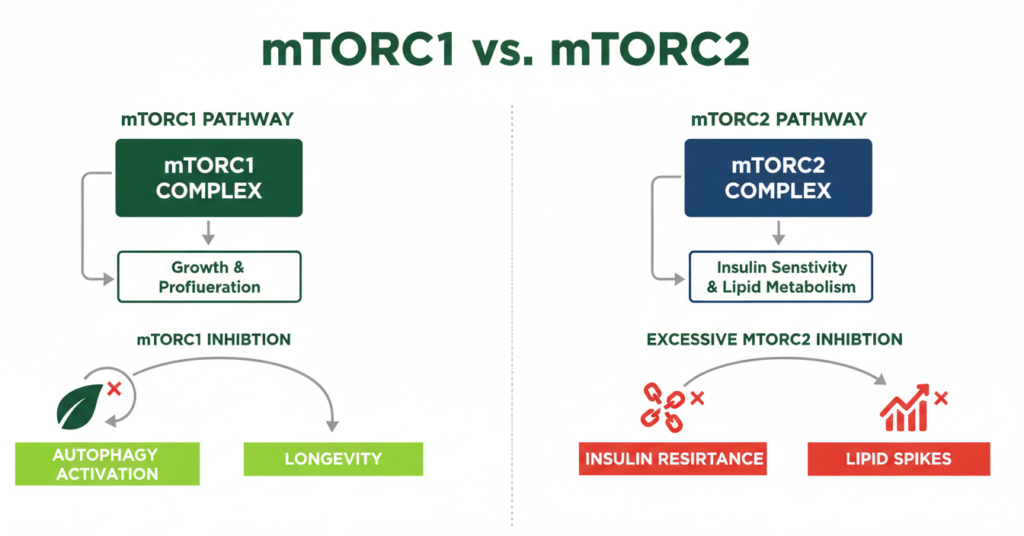

The metabolic impact of rapamycin on blood sugar is primarily a story of two complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2. While inhibiting mTORC1 is the intended goal for longevity to boost cellular cleanup (autophagy), prolonged exposure can disrupt mTORC2. In the liver, the loss of mTORC2 signaling impairs the ability of insulin to suppress glucose production, leading to hyperglycemia.

Recent studies in rats demonstrated that chronic treatment (2 mg/kg/day) promoted severe glucose intolerance and increased gluconeogenesis. This occurs even when insulin signaling appears preserved, uncoupling typical hormonal control from glucose homeostasis. Furthermore, rapamycin has been shown to reduce β-cell mass and impair insulin clearance, further complicating the glycemic profile.

However, the effect is highly dependent on the baseline metabolic state. In mouse models of Type 2 Diabetes (T2D), rapamycin treatment did not always exacerbate the condition; in some cases, it actually increased insulin sensitivity and reduced weight gain. This suggests that the “metabolic defect” of rapamycin may be a consequence of its action as a starvation-mimetic in otherwise healthy systems.

Does Rapamycin Increase Cholesterol and Triglycerides?

Yes, hyperlipidemia is one of the most documented side effects of Rapamycin, with clinical studies showing triglyceride increases exceeding 100% within six weeks of initiation. This effect is driven by the inhibition of lipid-handling enzymes, such as lipoprotein lipase (LPL), which impairs the clearance of fats from the bloodstream.

In both human transplant recipients and animal models, rapamycin-mediated inhibition of the mTOR pathway disrupts lipid metabolism. The drug coordinates a downregulation of genes involved in lipid uptake and storage in adipose tissue, causing fats to remain in circulation. This often manifests as hypertriglyceridemia and elevated LDL-cholesterol.

Expert consensus, including insights from Dr. Peter Attia and Dr. Matt Kaeberlein, highlights that these metabolic shifts are dose-dependent. For instance, severe cases of srlms-induced hypertriglyceridemia have seen levels spike to over 19,000 mg/dL in patients on immunosuppressive regimens, though such extremes are rare in low-dose longevity protocols.

Interestingly, some research suggests that these lipid elevations may be reversible upon cessation of the drug, returning to baseline within 1–2 weeks. This has led many in the biohacking community to favor intermittent dosing schedules to allow metabolic recovery.

The mTORC1 vs. mTORC2 Trade-off: Why Dosing Strategy Matters

To understand how much rapamycin should you take, one must understand the functional divide between the two mTOR complexes.

• mTORC1: The primary target for longevity. It regulates protein synthesis and autophagy. Its overactivation drives aging.

• mTORC2: Foundational for insulin signaling and cytoskeletal organization. Its inhibition is generally considered an “off-target” side effect in longevity medicine.

This separation creates a therapeutic window. Low-dose intermittent rapamycin (e.g., 5–10 mg once weekly for a 70 kg adult) is designed to selectively dampen mTORC1 while leaving mTORC2—and thus metabolic and immune function—largely intact. Chronic daily exposure, used in transplant medicine to prevent organ rejection, intentionally suppresses both complexes, which is why those populations experience more frequent metabolic disturbances.

What Biomarkers Should You Monitor While Taking Rapamycin?

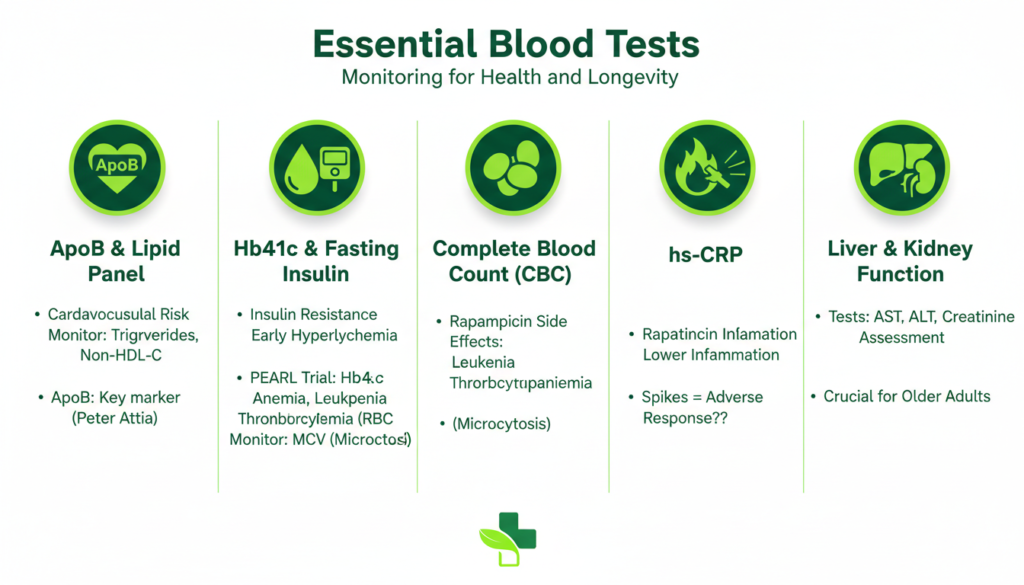

Given the drug’s impact on glucose and lipids, regular laboratory testing is essential for anyone using rapamycin off-label for healthspan extension.

| Biomarker | Purpose in Rapamycin Protocol | Target/Note |

| ApoB | Cardiovascular risk | Preferred over LDL-C |

| HbA1c | Long-term glucose control | Monitor for rising trends |

| Triglycerides | Lipid metabolism | Can increase significantly |

| MCV | Red blood cell health | Microcytosis is common |

| Cystatin C | Kidney health | More accurate than creatinine in some populations |

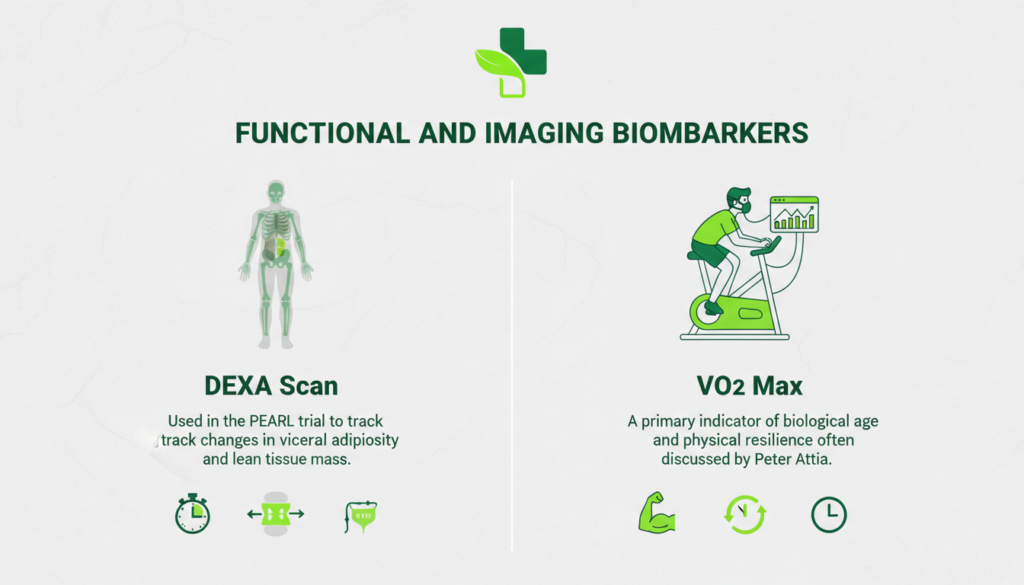

• DEXA Scan: Used in the PEARL trial to track changes in visceral adiposity and lean tissue mass.

• VO2 Max: A primary indicator of biological age and physical resilience often discussed by Peter Attia.

User Experience: Real-World Data on Side Effects

While model organisms show near-universal lifespan extension, rapamycin user reviews from the human longevity community reveal a mix of results.

In a survey of 333 adults taking rapamycin off-label, mouth sores (canker sores) were the most frequently reported side effect, affecting approximately 20–40% of users. These are typically transient and can often be managed by reducing the dose or increasing the interval between doses.

Interestingly, about 25–38% of users in this cohort reported subjective improvements in well-being, energy levels, and physical stamina.

Can You Take Rapamycin and Metformin Together?

Many longevity enthusiasts combine rapamycin and metformin to mitigate rapamycin’s glycemic side effects. Metformin, which activates AMPK, can improve insulin sensitivity and potentially counteract the glucose intolerance induced by rapamycin.

The NIA’s Interventions Testing Program (ITP) has investigated this combination in mice, finding that pairing the two can normalize insulin sensitivity and reduce complications of metabolic syndrome more effectively than either drug alone. However, Peter Attia classifies metformin as “fuzzy” due to inconsistent human data, suggesting that while the logic is sound, more robust human trials like the TAME trial are needed to confirm the synergy.

Conclusion: Balancing Risk and Reward

Rapamycin remains a “promising” rather than “proven” tool for human longevity. Its metabolic effects are a double-edged sword: it can rejuvenate the heart, immune system, and skin, but it can also raise blood sugar and cholesterol if the dosing is too aggressive.

The current evidence favors a “start low, go slow” approach, utilizing weekly dosing schedules to prioritize mTORC1 selectivity. For those considering this path, meticulous monitoring of ApoB, HbA1c, and CBC is non-negotiable.

Key Takeaways:

• Dose Frequency: Intermittent (weekly) dosing is theorized to be safer and more effective for longevity than daily use.

• Metabolic Risks: Monitor for rising triglycerides and impaired glucose tolerance.

• Synergy: Combining with exercise and potentially metformin may help mitigate side effects.

• Medical Oversight: Never initiate rapamycin without clinical partnership and routine lab work.

No, in the context of longevity, it is a geroprotector or mTOR inhibitor1. While it is used as an adjuvant in oncology, its longevity application involves far lower doses.

Contraindications include severe hepatic impairment, uncontrolled hyperlipidemia, primary immune deficiencies, or situations where impaired wound healing is risky (e.g., major surgery).

Yes, veterinary research through the Dog Aging Project is actively studying its effects on canine lifespan, and some veterinarians prescribe it off-label.

There is anecdotal “biohacker” interest in this, but peer-reviewed clinical evidence for reversing gray hair in humans is currently lacking.

Resource links

Therapeutic drug monitoring, electronic health records, and pharmacokinetic modeling to evaluate...

About-face on the metabolic side effects of rapamycin

Chronic Rapamycin Treatment Causes Glucose Intolerance and Hyperlipidemia...

Rapamycin for longevity: the pros, the cons, and future perspectives

Rapamycin-Induced Insulin Resistance Is Mediated by mTORC2 Loss and Uncoupled from Longevity

Rapamycin treatment benefits glucose metabolism in mouse models of type 2 diabetes

Effects of Post-Transplant Drugs on Lipids and Treatment Options

Rapamycin up-regulates triglycerides in hepatocytes by down-regulating Prox1

“Anti-Aging” Drugs — NAD+, metformin, & rapamycin

Reviewing 15 years of experience with sirolmus

Rapamycin does not compromise physical performance or muscle hypertrophy...

Understanding and Managing Rapamycin Side Effects: A Comprehensive Guide

The biomarkers recommended by Peter Attia in Outlive

Safety and efficacy of rapamycin on healthspan metrics after one year: PEARL Trial Results

Potential Impact of Infusion Technique on Drug Delivery

New Insights into Red Blood Cell Microcytosis upon mTOR Inhibitor Administration

Evaluation of off-label rapamycin use on oral health

Evaluation of off-label rapamycin use to promote healthspan in 333 adults

Targeting ageing with rapamycin and its derivatives in humans: a systematic review