Molecular Gatekeeping: How Rapamycin Inhibits mTORC1

The study of the Mechanistic Target Of Rapamycin (mTOR) has evolved from a curious discovery in Easter Island soil to the cornerstone of modern longevity science. While early research focused on its immunosuppressive properties, current clinical interest centers on its role as the “master regulator” of cellular growth and aging. Understanding the precise structural mechanism of how rapamycin inhibits the mTORC1 pathway is no longer just a concern for biochemists; it is essential for developing safe protocols for human healthspan extension. This guide deep-dives into the “molecular gatekeeping” model, the structural realities of substrate recruitment, and the critical differences between first-generation rapalogs and emerging third-generation inhibitors.

How does Rapamycin inhibit the mTORC1 pathway?

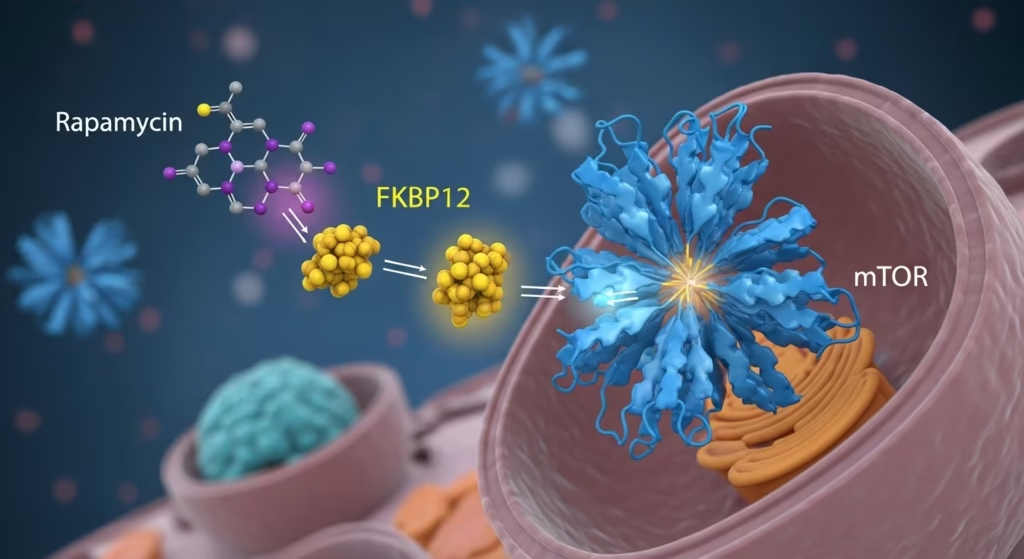

Rapamycin is often called an “inhibitor,” but that term is a bit of a misnomer. In reality, Rapamycin is a molecular glue. It doesn’t just block a site; it creates a new protein-protein interaction that acts as a physical gatekeeper.

Rapamycin first grabs the helper protein (FKBP12). This pair then lands on a specific “docking station” on the mTOR protein called the FRB domain. Once all three are joined, they act like a physical lid or cap over the mTOR protein’s “engine” (the active site). This cap is so tight that it blocks large growth signals from getting inside, effectively locking the door to cellular growth.

1. The “Ternary Complex” Mechanism

Unlike most drugs that bind directly to their target, Rapamycin requires an “accomplice.” It acts like a piece of “molecular glue”.

• Rapamycin: The drug itself.

• FKBP12: A “helper” protein already inside your cells.

• mTOR: The target protein that controls growth.

Step 1: Once Rapamycin enters the cell, it binds to a small chaperone protein called FKBP12 (12 kDa FK506-binding protein).

Step 2: The resulting Rapamycin-FKBP12 complex then hunts down the FRB domain (FKBP12-Rapamycin Binding domain) on the mTOR protein.

Step 3: By binding to the FRB domain, it forms a Ternary Complex. This complex sits right at the “mouth” of the mTOR catalytic site, physically preventing specific substrates from getting close enough to be phosphorylated.

The architecture of mTOR is massive, comprising over 2,500 amino acids organized into distinct domains. Within this domain, a specific hydrophobic pocket is the primary docking site for the rapamycin macrolide.

Research indicates that the FRB domain acts as a “molecular gatekeeper”. Under normal conditions, the FRB domain uses its rapamycin-binding site to interact with substrates, granting them “privileged access” to the recessed catalytic center. When rapamycin occupies this site, it hijacks the gatekeeping mechanism, effectively locking the door to the enzyme’s active site for most downstream growth-promoting substrates.

2. Allosteric vs. Competitive Inhibition

Competitive inhibition occurs when a molecule binds directly to the active site of an enzyme, physically preventing the substrate from entering. In the context of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), ATP-competitive inhibitors (such as Torin-1 or RapaLink-1) bind to the ATP-binding site within the kinase domain. This prevents the transfer of phosphate groups to substrates, effectively shutting down catalytic activity.

A competitive inhibitor is like a fake key that fits into the lock but won’t turn. Because the fake key is stuck in the lock, the real key can’t get in, and the engine stays off.

Allosteric inhibition traditionally refers to an inhibitor binding at a site remote from the kinase active site, inducing a conformational change that reduces enzymatic activity. Rapamycin has long been classified as an allosteric inhibitor because it binds to the FKBP12-rapamycin-binding (FRB) domain, which is adjacent to, rather than within, the catalytic cleft.

Alosteric inhibition is like putting a heavy lid over the entire lock so the key can’t even reach it

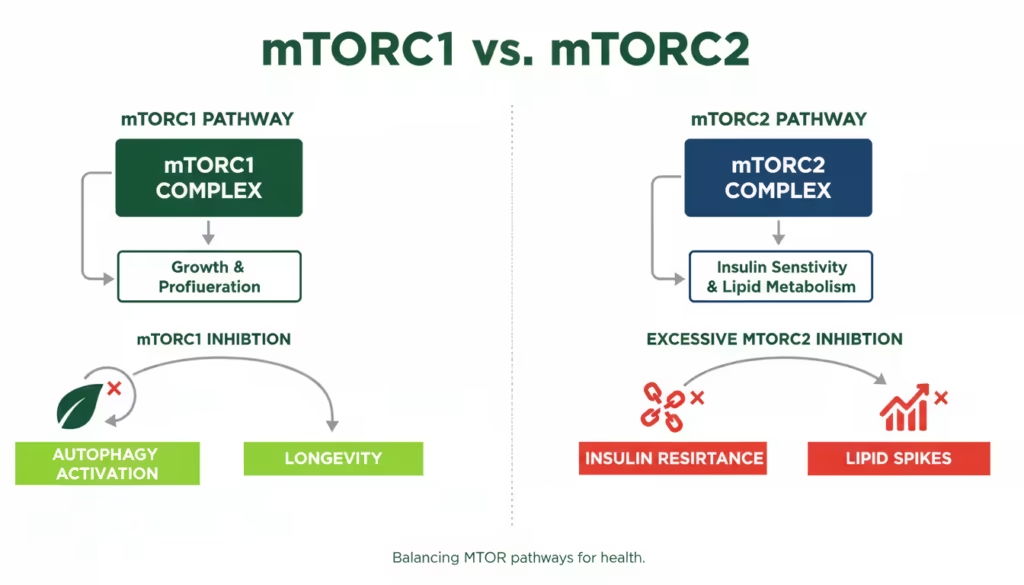

3. The Selectivity Mystery: Why Not mTORC2?

Why Rapamycin hits mTORC1 but ignores its sibling, mTORC2, in the short term?

Rapamycin selectively inhibits mTORC1 in the short term because its mechanism of action requires the formation of a ternary complex with the intracellular protein FKBP12, which specifically docks onto the FRB (FKBP12-rapamycin-binding) domain of the mTOR kinase. In the structural architecture of mTORC1, this domain is accessible, allowing the FKBP12-rapamycin complex to act as a physical “cap” that occludes the catalytic cleft and interferes with substrate recruitment.

While rapamycin does not bind directly to the pre-assembled mTORC2 complex, chronic administration can inhibit mTORC2 assembly by sequestering the “free pool” of mTOR subunits. The danger lies in the metabolic side effects. mTORC2 is a critical regulator of the Akt pathway, which modulates insulin sensitivity. When mTORC2 is inhibited in the liver and other tissues, it can mirror the symptoms of metabolic syndrome, including elevated blood glucose and disrupted lipid profiles.

• mTORC1 is open: It has its “docking station” (the FRB domain) sitting right out in the open. Rapamycin and its helper protein can land there easily and put on the “cap” to stop growth.

• mTORC2 has the Barrier Architecture: This sibling is built with extra “armor” proteins (like Rictor) that wrap around it. This armor hides the docking station, so rapamycin simply has nowhere to land.

Note: Rapamycin only affects the mTORC2 sibling if you take it for a long time (usually over 24 hours). It doesn’t “attack” the assembled mTORC2; instead, it grabs the spare parts of mTOR before they can even be built into a new mTORC2 complex.

4. Substrate Selectivity: The “Leaky” Inhibition

Substrate selectivity, often referred to in longevity science as “leaky” inhibition, describes the phenomenon where rapamycin does not completely shut down the mTORC1 complex. Instead, it acts as a partial or incomplete inhibitor, blocking certain cellular growth signals while allowing others to continue functioning.

Even within mTORC1, Rapamycin doesn’t stop everything. It is “leaky,” which is actually its greatest longevity secret. While the larger substrates, such as S6K1, are physically too big to bypass this cap and are therefore completely inhibited, smaller substrates or those with high-affinity docking mechanisms can still reach the catalytic center -“leak” through the inhibition- and does not totally abolish critical survival functions like autophagy or all aspects of protein synthesis.

Why this matters for 2026: If Rapamycin blocked 4E-BP1 as effectively as it blocks S6K1, it might be too toxic. This “imperfect” inhibition is what allows for the rejuvenative state—slowing the junk-building process while keeping essential survival signals intact.

Conclusion: The Future of Molecular Gatekeeping

The discovery that the FRB domain acts as a gatekeeper for mTORC1 has revolutionized the approach to anti-aging pharmacology. We now know that rapamycin does not just “turn off” mTOR; it subtly reshapes how the enzyme interacts with the cell’s internal environment.

Key Takeaways:

• Mechanism: Rapamycin creates a physical block on the FRB domain, preventing growth-related substrates from being recruited.

• Differential Effects: It is a complete inhibitor for some pathways (S6K) but an incomplete one for others (4E-BP1/Autophagy).

• mTORC2 Risks: Chronic dosing carries the risk of metabolic disruption, necessitating a pulsatile or “on-off” dosing cycle.

Rapamycin primarily inhibits mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1), which controls protein synthesis, ribosome biogenesis, and autophagy. It is less effective at inhibiting mTOR Complex 2 (mTORC2) unless used chronically.

While Rapamycin induces autophagy by inhibiting mTORC1, there is no clinical “gold standard” for the length of a fast. However, nutrient withdrawal naturally suppresses mTORC1 via the Rag GTPase pathway, potentially synergizing with Rapamycin’s gatekeeping effect.

The answer depends on the dosing protocol. Acute treatment specifically disables mTORC. However, prolonged exposure allows rapamycin to bind to newly synthesized mTOR molecules before they can be incorporated into the mTORC2 complex (which requires the Rictor protein instead of Raptor).

Resource links

The Target of Rapamycin and Mechanisms of Cell Growth

mTOR as a central regulator of lifespan and aging

Characterization of the FKBP.rapamycin.FRB ternary complex

Discovery of fully synthetic FKBP12-mTOR molecular glues†

Dissecting the biology of mTORC1 beyond rapamycin

mTOR kinase structure, mechanism and regulation by the rapamycin-binding domain

Cryo-EM insight into the structure of MTOR complex 1 and its interactions with Rheb and substrates

Structure of the human mTOR Complex I and its implications for rapamycin inhibition

mTORC1 and CK2 coordinate ternary and eIF4F complex assembly

Structural Mechanisms of mTORC1 activation by RHEB and inhibition by PRAS40