Rapamycin and Cancer Prevention: The mTOR Connection

For many people interested in living longer, the goal is simple: avoid the “Big Four” diseases of aging. At the top of that list is cancer. Modern science is moving away from just treating cancer after it appears and toward Rapamycin and cancer prevention as a way to stop the disease before it even starts.

Researchers now believe that the same biological “engine” that drives aging also drives cancer. By slowing down this engine with a drug called Rapamycin, we may be able to delay the onset of tumors and extend our healthy years.

What does Rapamycin inhibit in the human body?

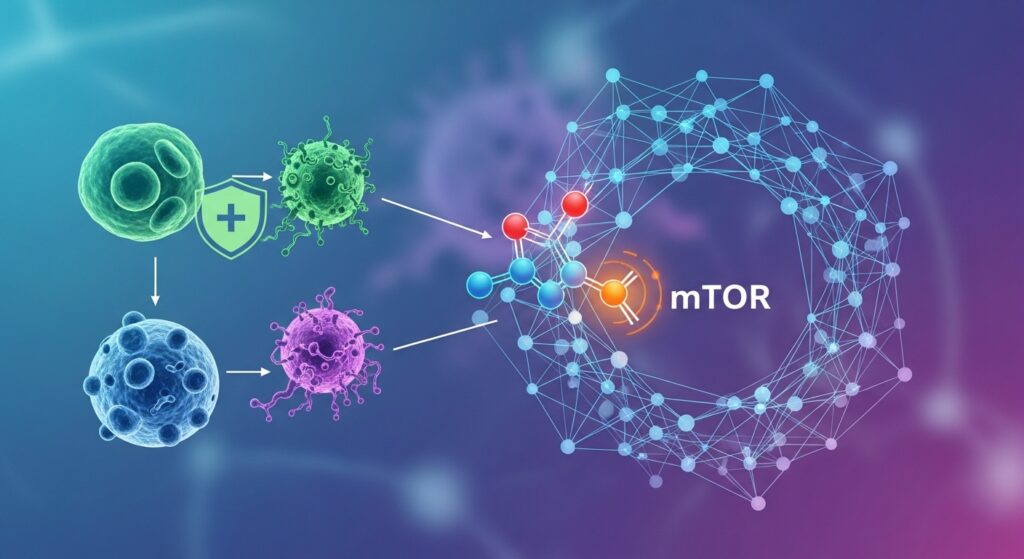

Rapamycin inhibits a protein called mTOR (mechanistic Target of Rapamycin), which acts like a “general contractor” for your cells. It is a nutrient sensor that tells cells when to grow and divide; when Rapamycin blocks mTOR, it tells the cells to stop growing and start a deep-cleaning process called autophagy.

In a healthy young person, mTOR is essential for building muscle and developing the body. however, as we age, mTOR can become overactive. This constant “growth” signal is a major problem because it can lead to uncontrolled cell division—which is the definition of cancer. By inhibiting mTOR, rapamycin essentially turns down the volume on these growth signals, helping cells stay in a stable, resting state known as quiescence instead of turning into dangerous, fast-growing cancer cells.

Is Rapamycin chemotherapy or a different kind of drug?

Short answer is No. Rapamycin is not standard chemotherapy. While traditional chemotherapy is “cytotoxic” (meaning it is designed to kill cells), rapamycin is mostly “cytostatic,” meaning it simply slows cell growth and division down without necessarily killing the cell.

This is a vital distinction for rapamycin and cancer prevention. Rapamycin’s mechanism is not to kill every cell in the body to prevent cancer; but will work through to slow down the rate at which “pre-cancerous” cells turn into actual tumors. In studies with mice, Rapamycin robustly prevented cancer caused by cigarette smoke chemicals, not by killing the cells, but by reducing how fast they multiplied. Because it doesn’t kill cells in the same way. Even in higher does than for advised as a longevity supplement, Rapamycin has a much milder side-effect profile than standard chemo.

In summary, Rapamycin is considered a gerosuppressant that slows the biological clock of the cell, whereas chemotherapy acts as a toxin designed to destroy the cell’s ability to exist.

Speed and Nature of Response

Because Rapamycin is cytostatic, it often acts as a disease stabilizer rather than causing immediate tumor regression.

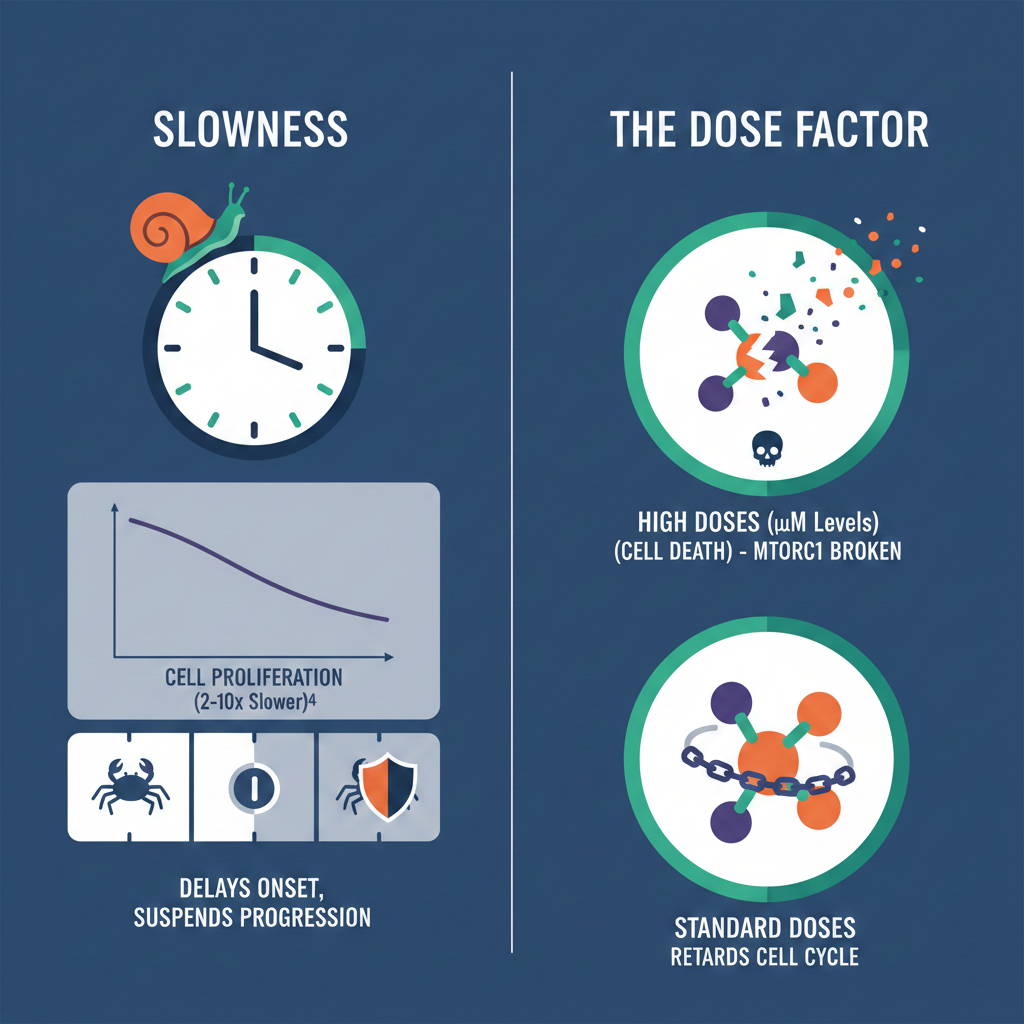

• Slowness: In cell cultures, rapamycin has been shown to slow cell proliferation 2–10 fold. It delays the onset of cancer and suspends the progression of low-grade tumors rather than eradicating them instantly.

• The Dose Factor: High doses of rapamycin (micromolar levels) can induce apoptosis (programmed cell death) by completely breaking apart cellular complexes (mTORC1), but standard doses generally only retard the cell cycle.

Absorption and Systemic Safety

The BC001 protocol highlights a major safety difference in how these drugs are absorbed and their side effects:

• Systemic Absorption: In the bladder cancer model, Rapamycin is expected to have minimal or no systemic absorption through the bladder wall due to its large molecular weight (~900 daltons) and nanoparticle size.

• Toxicity Profiles: Conventional chemotherapy often carries risks of myelosuppression (immune system shutdown) when given systemically. In contrast, the protocol notes that while Rapamycin must be handled with the same caution as cytotoxic drugs, its local administration is associated with much milder grade 1/2 local side effects (like frequent urination) rather than severe systemic toxicity.

Synergy in Combination

The BC001 protocol differentiates them by how they are used together. It notes that nab-rapamycin “bolsters” the efficacy of gemcitabine920. In this strategy, the rapamycin prepares the environment or slows the tumor cells, making the “killing” action of the cytotoxic chemotherapy more effective than if the chemo were used alone9.

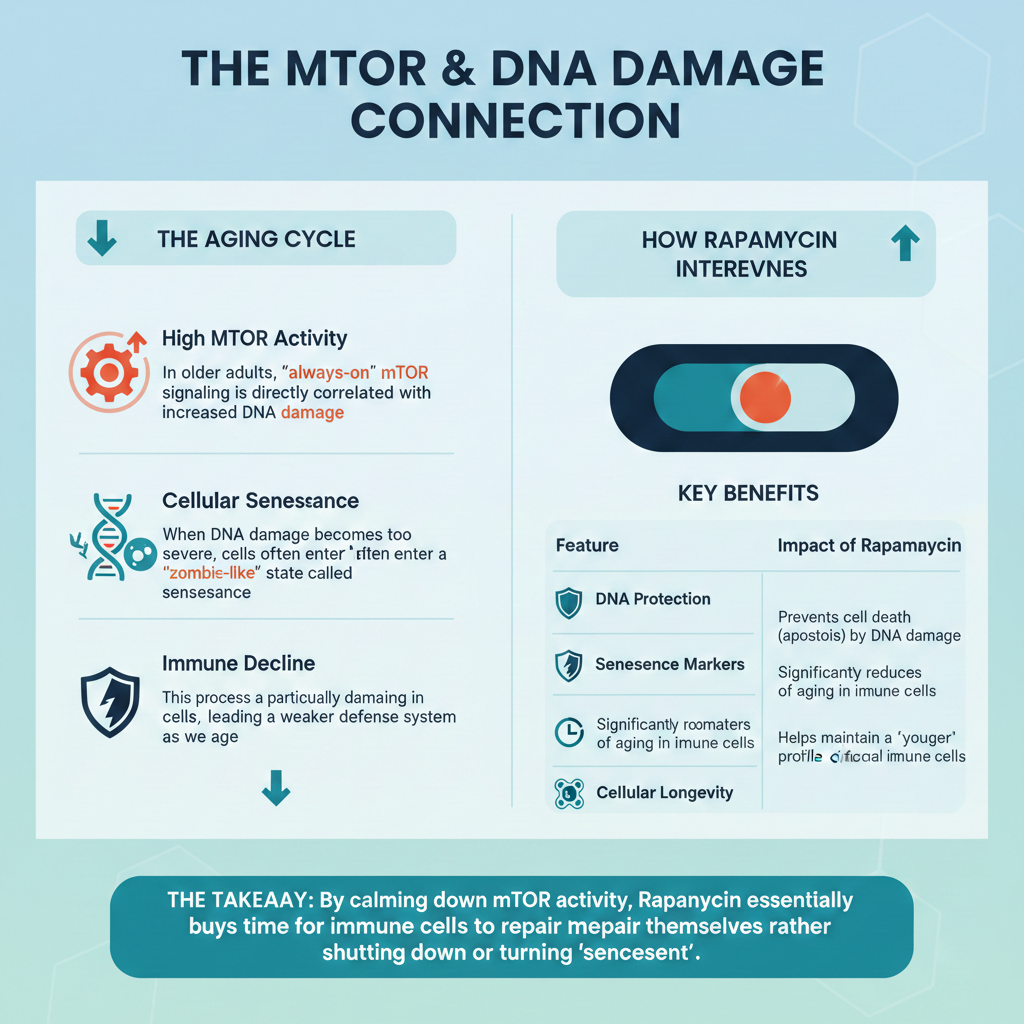

How does Rapamycin stop “Zombie Cells” from causing cancer?

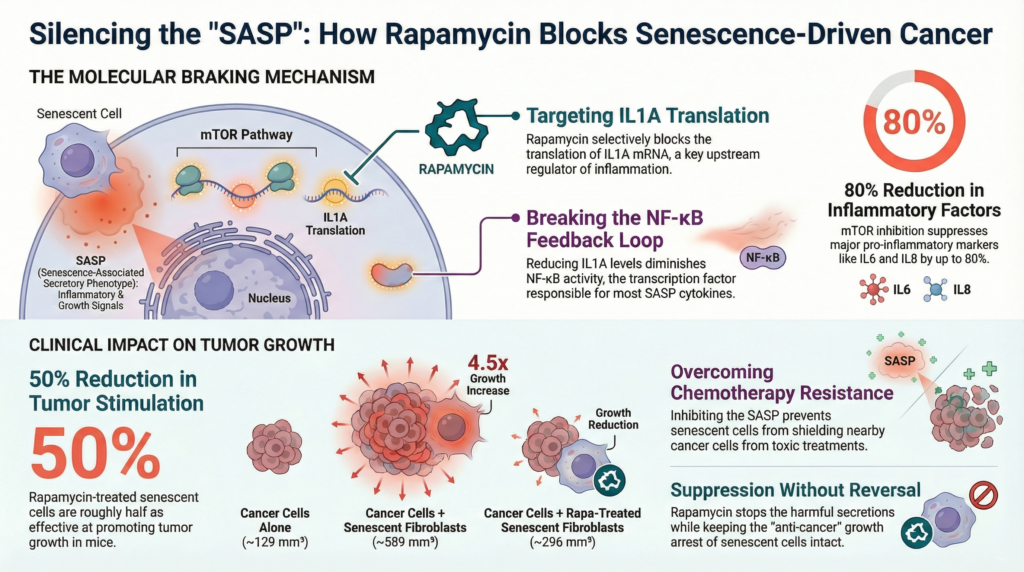

Senescent cells, often called “zombie cells,” are cells that have stopped dividing to prevent themselves from becoming cancerous However, as they age, they begin to leak a “toxic soup” of inflammatory proteins that can ironically help neighboring cells turn into tumors.

Rapamycin protects “normal” stem cells from being turned into these harmful zombie cells (a process scientists call geroconversion) through the following steps:

• Blocking the Master Controller: Rapamycin inhibits a protein called MTOR, which acts as a master switch for the zombie cell’s harmful secretions.

• Shutting Off the “Master Signal”: Specifically, Rapamycin prevents the cell from producing IL1A, a key inflammatory protein. IL1A normally acts as a leader that triggers the release of many other harmful chemicals.

• Breaking the Inflammatory Loop: By stopping IL1A, Rapamycin breaks the communication loop that keeps the zombie cell in a highly inflammatory state.

• “Muffling” the Cell: Once this signaling is shut down, the zombie cell stops producing the factors that help tumors grow, move, and resist chemotherapy.

By keeping the environment around your cells clean and low-inflammation, Rapamycin makes it much harder for a random mutation to turn into a deadly tumor. Rapamycin does not make the zombie cells start dividing again. It simply “silences” their harmful behavior, keeping them safely retired while preventing them from “poisoning” the surrounding tissue.

How much Rapamycin should I take for cancer prevention?

There is no “perfect” dose yet for humans, but most longevity experts, suggest low, weekly doses (e.g., 5mg to 10mg once a week). This is very different from the high, daily doses used for organ transplant patients.

This brings us to the “Enigma of Rapamycin Dosage“. Scientists have found that different doses do different things:

• Low Doses (Nanomolar): These are usually enough to stop cells from growing too fast by blocking a signal called S6K1.

• High Doses (Micromolar): You need much higher doses to block a different signal called 4E-BP1, which is the signal cells use to actually build the proteins required for a tumor to survive.

Because high daily doses can cause side effects like high cholesterol or mouth sores, the goal for prevention is often to find the lowest possible dose that still triggers autophagy and blocks the SASP.

If you are looking for more information about Rapamycin Dosing for Longevity, please visit our blog post from here.

Are there specific MTOR mutations that make Rapamycin work better?

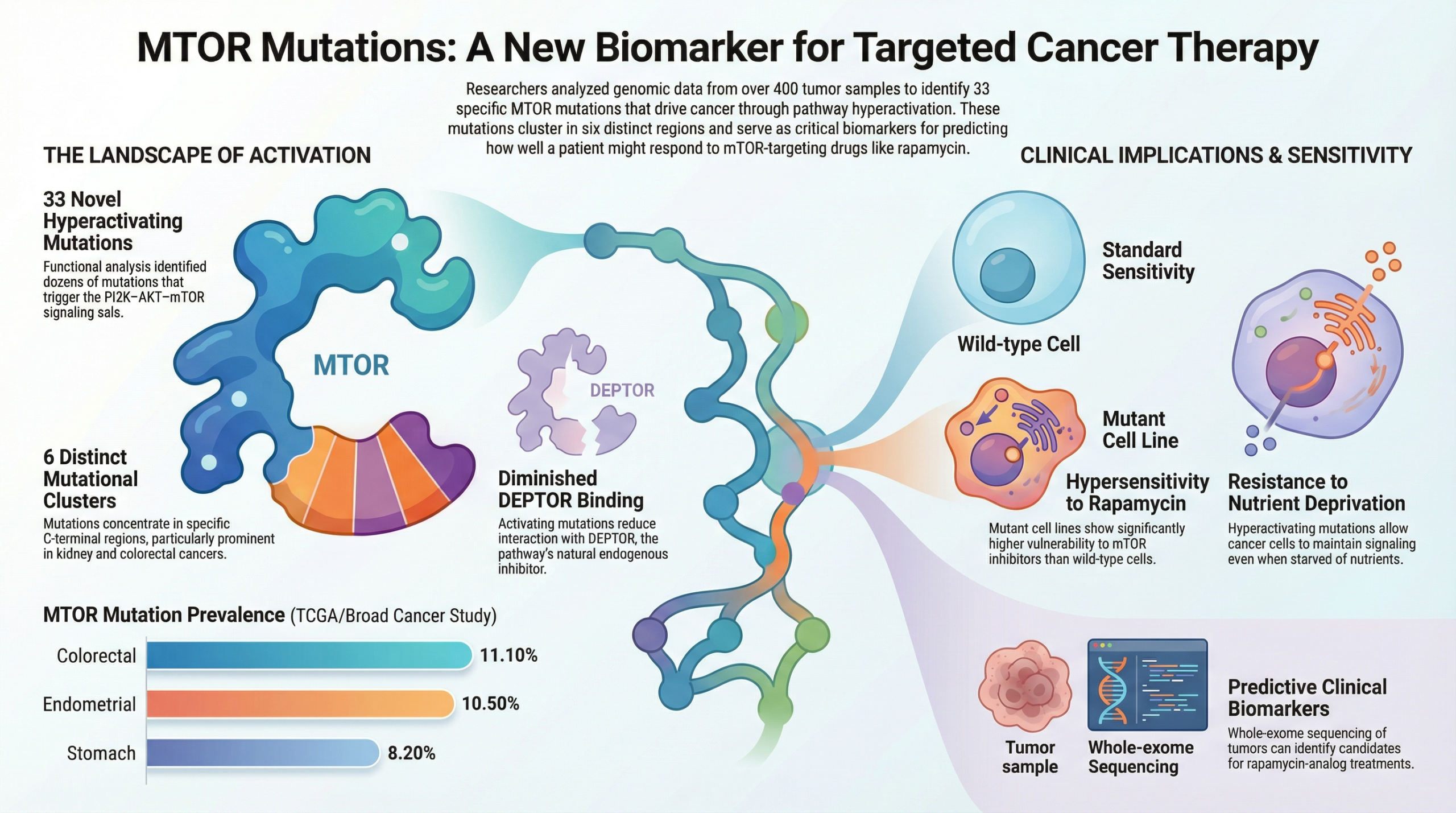

Specific mutations in the MTOR gene that cause pathway hyperactivation significantly influence how cancer cells respond to treatment, primarily by increasing their sensitivity to mTOR inhibitors like Rapamycin.

Scientists have identified 33 specific MTOR mutations that make certain cancers “addicted” to the mTOR pathway. If a patient has one of these mutations, their cancer is often hypersensitive to Rapamycin, making the drug much more effective. These mutations affect drug sensitivity in the following ways:

• Increased Drug Sensitivity: Because these cancer cells become “addicted” to this constant growth signal, they are highly sensitive to drugs that shut that signal off, such as rapamycin. In studies, cancer cells with these mutations were much easier to kill with these drugs than cells without them.

• Resistance to Starvation: While these mutations make the cells easier to kill with medicine, they make them harder to kill through natural means. Mutated cells can keep growing even when starved of nutrients (like sugar), a condition that would normally cause healthy cells to stop growing.

• A Guide for Treatment: Because these specific mutations predict a strong response to certain drugs, they can be used as biomarkers. This allows doctors to test a patient’s tumor to see if they are likely to be an “extraordinary responder” to mTOR-targeting therapies.

In short, these mutations create a weakness that drugs can exploit, but they also give the cancer a survival advantage in harsh, nutrient-poor environments.

In the future, doctors may use genetic testing to see if a person has these mutations (like S2215Y or E1799K) to decide if they are a good candidate for Rapamycin and cancer prevention. This is the beginning of “personalized prevention,” where we use a person’s DNA to determine their exact anti-aging protocol.

Conclusion

The connection between rapamycin and cancer prevention is one of the most exciting areas in modern medicine. By turning down the “growth switch” of mTOR, rapamycin helps our bodies clean out cellular trash through autophagy, stops toxic “zombie cells” from causing inflammation, and slows the overall clock of biological aging.

While we are still learning the exact “best dose,” the PEARL trial and other research suggest that low, weekly doses are a safe way for many people to potentially lower their cancer risk and maintain muscle mass as they age.

The PEARL trial showed that low doses (around 3mg/week) are generally safe for healthy adults over 50, but it can cause mild side effects like mouth sores or higher blood sugar in some people.

In the PEARL trial, there was no major change in “visceral fat” (belly fat), but women did see an increase in lean muscle mass.

Mouse studies suggest that starting early in life provides the biggest benefit for preventing tumors and extending life. However, most human studies focus on adults over age 50.

It is most effective against cancers that “depend” on the mTOR pathway, such as certain lung, breast, and kidney cancers.

Resource links

Cancer prevention with rapamycin

The Role of Autophagy in Cancer: Therapeutic Implications

New Oxford Study: Powerful Longevity Drug Rapamycin Targets Cell Senescence

Clinical Study Protocol: BC001 (Bladder Cancer)

Safety and efficacy of rapamycin on healthspan metrics after one year: PEARL Trial Results