Clinical Trials Update: Current Human Studies on Rapamycin and Longevity

For decades, the search for a true “longevity pill” was considered more science fiction than science. However, the discovery of the mTOR pathway and its inhibition by a soil-derived molecule called rapamycin has shifted that perspective. While animal studies have long shown that rapamycin can extend lifespan by up to 60%, the question of whether these benefits translate to humans is only now being answered through rigorous clinical research.

Human studies on rapamycin and longevity are currently at a critical junction, moving from small safety pilots to longer-term evaluations of “healthspan”—the period of life spent in good health. This blog provides a comprehensive update on the latest clinical trials, expert opinions, and real-world data surrounding this promising longevity intervention.

What are the Most Recent Findings from the PEARL Trial?

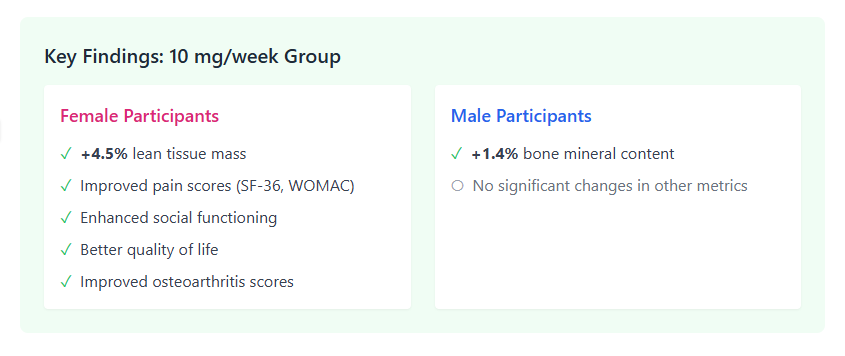

The Participatory Evaluation of Aging with Rapamycin for Longevity (PEARL) trial is the longest study to date evaluating the safety of intermittent, low-dose rapamycin in healthy older adults. The trial demonstrated that weekly doses of 5 mg and 10 mg are generally safe and well-tolerated over 48 weeks, though the benefits were highly sex-specific. Specifically, the 10 mg dose was associated with significant improvements in lean muscle mass for women and bone mineral content for men.

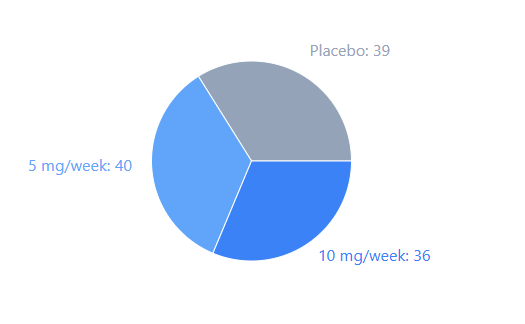

FIGURE-1: PEARL, Participant Distribution

The PEARL trial involved 115 participants aged 50 to 85, making it a landmark in the field of geroprotection. While the study did not show a massive reduction in visceral fat (the primary goal), the improvements in physical health markers were encouraging.

CHART-1: PEARL, Key Findings

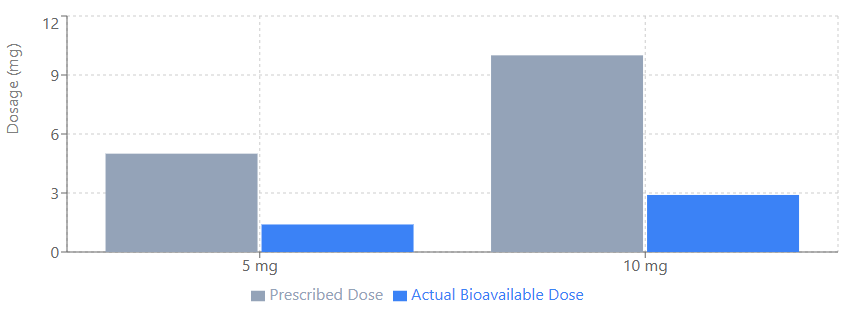

However, a major realization during the trial was the issue of bioavailability. Researchers discovered that the compounded rapamycin used in the study had approximately one-third the bioavailability of generic, commercially available versions. This means the 5 mg and 10 mg weekly doses were effectively equivalent to roughly 1.4 mg and 2.9 mg of standard product. Despite these effectively lower doses, women in the 10 mg group gained an average of 0.5 pounds of lean mass per month, suggesting rapamycin may help combat age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia).

FIGURE-2: Actual vs. Prescribed Rapamycin Dosage in PEARL Study

Can Rapamycin Improve Immune Function in Older Adults?

Contrary to its historical label as an “immunosuppressant,” low-dose rapamycin appears to act as an “immunomodulator” that can actually rejuvenate the immune system. Landmark trials by Mannick et al. showed that short-term treatment with rapalogs (rapamycin derivatives) enhanced the immune response to influenza vaccines by approximately 20% in the elderly. This improvement is likely due to the reduction of “exhausted” T cells that typically accumulate with age.

The distinction between high-dose transplant medicine and low-dose longevity protocols is vital. While high daily doses (2–5 mg/day) are used to prevent organ rejection, low intermittent doses (5 mg once weekly) target only the mTORC1 complex while leaving mTORC2 relatively unaffected.

Key findings from these studies include:

• Reduced Infection Rates: A 2018 study found that TORC1 inhibition was associated with a significant decrease in annualized infection rates among elderly subjects.

• Antiviral Gene Upregulation: Low-dose combinations of mTOR inhibitors were found to upregulate interferon-induced antiviral genes, potentially providing better defense against respiratory viruses.

• Reversibility: The “side effects” typically feared by clinicians, such as hyperglycemia or hyperlipidemia, were lower in the treatment groups than in the placebo groups during these low-dose trials.

What do clinical trials show about rapamycin and Alzheimer’s?

Clinical evidence for rapamycin in treating Alzheimer’s disease is mixed and suggests that timing is everything. While small pilots have shown that rapamycin is safe for patients with mild cognitive impairment, recent data from the Gonzales et al. Phase 1 trial found that an 8-week course of 1 mg/day failed to reach detectable levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF)3. Furthermore, some biomarkers of neurodegeneration, such as p-tau 181 and NfL, actually increased after treatment in this specific cohort.

Experts like Dr. Mitzi Gonzales suggest that rapamycin may be more effective for prevention rather than treatment. In prevention trials involving middle-aged APOE4 carriers (those at higher genetic risk for AD), rapamycin was found to reduce inflammatory cytokines and increase cerebral blood flow—effects not seen in non-carriers or late-stage patients.

The current consensus is that:

1. Low doses may not penetrate the brain effectively unless the blood-brain barrier is already compromised by disease.

2. Early intervention is likely required, as animal studies show that rapamycin can prevent plaques from forming but struggles to clear them once established.

3. Microglial activation may be suppressed by rapamycin, which could be detrimental in some models (like the 5XFAD mouse) where microglia are needed to clear amyloid plaques.

Is Rapamycin Safe for Long-term Use in Healthy Humans?

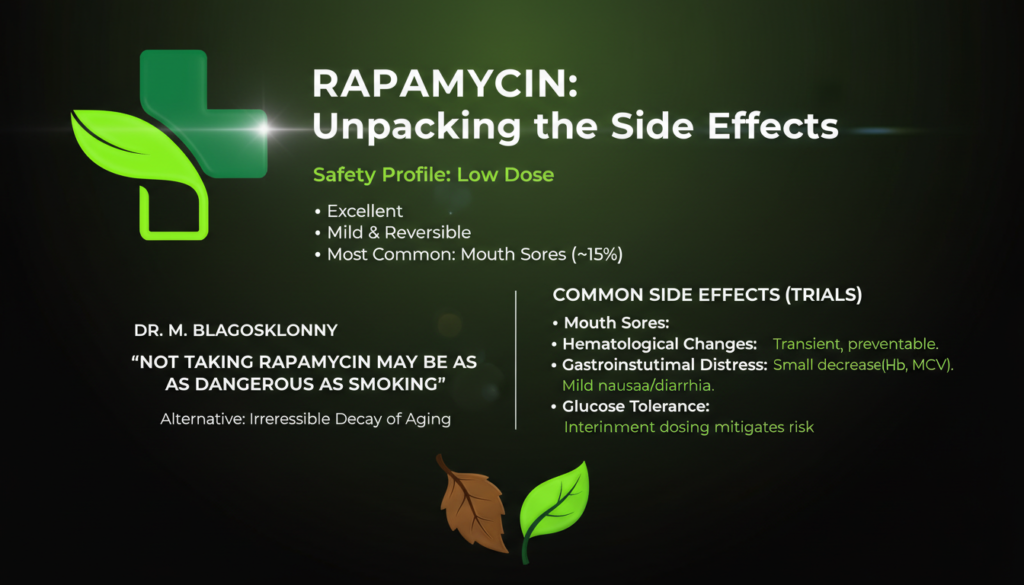

The safety profile for rapamycin at low doses is currently viewed as excellent, with most side effects being mild and reversible. In surveys of 333 off-label users, the most common side effect was mouth sores (stomatitis), reported by about 15% of users. Other “side effects” like elevated cholesterol are usually minor and can be managed through diet or temporary discontinuation of the drug.

Dr. Mikhail Blagosklonny, a leading advocate for the drug, argues that “not taking rapamycin may be as dangerous as smoking” for the elderly because the drug targets the root causes of age-related death. He emphasizes that the alternative to rapamycin’s reversible side effects is the irreversible decay of aging.

Common Side Effects reported in trials:

FIGURE-2: Rapamycin’s Safety Profile

• Mouth Sores: Usually transient and preventable by adjusting the dose.

• Hematological Changes: Small decreases in hemoglobin and red blood cell volume (MCV).

• Gastrointestinal Distress: Mild nausea or diarrhea in a small percentage of users.

• Glucose Tolerance: While high doses can cause insulin resistance, intermittent dosing (once weekly) appears to minimize this risk.

What are the Most Effective Rapamycin Dosing Protocols?

Because no FDA-approved protocol for longevity exists, current regimens are based on “geroscience guesswork” that combines animal data with human safety profiles. The most common approach used by practitioners is “pulse dosing”—taking the drug once per week to allow mTOR inhibition to be followed by a period of mTOR reactivation. This reactivation is thought to be necessary for normal stem cell function and muscle repair.

Current Dosing Trends:

1. Weekly Dosing: The standard of 5–7 mg once weekly is the most popular schedule, generally lacking systemic side effects.

2. Daily Low-Dose: Some trials have tested 0.5 mg to 1 mg daily, which is also well-tolerated but carries a higher risk of inhibiting mTORC2, leading to metabolic disruptions.

3. Transient Dosing: Short cycles, such as 12 weeks of treatment followed by a long “washout” period, have shown persistent benefits in mice and are being explored in humans.

Subscription services and online longevity clinics now offer rapamycin to US customers, often requiring regular blood monitoring of lipids and glucose to ensure safety. Expert Dr. Matt Kaeberlein suggests that while we don’t know the “perfect” dose, the current once-weekly range of 3–6 mg appears to sit within a safe “therapeutic window” for most people.

| Trial Name | Population | Dose | Key Findings |

| PEARL | Healthy adults (50-85) | 5-10mg/week | Improved muscle in women; bone in men; safe for 48 weeks. |

| Mannick (RAD001) | Elderly (65+) | 5mg/week | 20% better vaccine response; fewer infections. |

| Gonzales (AD) | MCI / AD Patients | 1mg/day | No CSF detection; safety confirmed; mixed biomarkers. |

| UW Survey | Off-label users | Variable | High reported well-being; mouth sores common. |

| RAP-ALS | ALS Patients | 1-2mg/m² daily | No effect on Tregs; well-tolerated. |

TABLE-1: Comparison of Major Human Rapamycin Trials

Real-World Insights: User Experiences and Testimonials

Beyond the sterile environment of the laboratory, the biohacking community has provided a wealth of anecdotal evidence. In the UW Rapamycin Study, 333 off-label users reported significant subjective improvements in their quality of life.

Commonly reported benefits from users include:

• Increased Energy and Stamina: Many users aged 48–65 report running longer and recovering faster from workouts.

• Reduced Joint Pain: Users often find that chronic aches, potentially related to age-induced inflammation, resolve within 2–3 months.

• Improved Mood: A significant number of participants reported feeling “happier,” “calmer,” and “less anxious”.

• Skin and Hair Health: Testimonials mention smoother skin and occasional darkening of grey hair, though these are not yet scientifically validated.

It is important to note that these reports are self-reported and may be subject to the placebo effect. However, the ratio of those reporting “improved health” versus “worsened health” in these surveys is over 7:1, indicating a strong trend of perceived benefit.

Conclusion: The Path Forward

The current state of human clinical trials suggests that low-dose rapamycin is safe and holds real potential for slowing markers of biological aging. While it may not be a “cure” for late-stage diseases like Alzheimer’s, its ability to rejuvenate the immune system and protect muscle mass makes it a foundational tool in the future of geromedicine.

As research continues, the focus will shift toward personalized dosing based on individual biomarkers. Until larger, well-powered trials are completed, individuals interested in rapamycin for longevity should work closely with experienced physicians to balance the promising benefits with the known side effects.

Do you want to live a longer life in good health? Stay informed on the latest geroscience breakthroughs by consulting with a longevity specialist today.

Resource links

Rapamycin for longevity: opinion article, PubMed

Low-dose rapamycin shows promise for enhancing healthspan in older adults

First Results from the PEARL Trial of Rapamycin

Anti-Aging Supplement Rapamycin Slows Muscle and Bone Aging in First Long-Term Clinical Trial

Participatory Evaluation (of) Aging (With) Rapamycin (for) Longevity Study (PEARL)

Influence of rapamycin on safety and healthspan metrics after one year: PEARL trial results

mTOR inhibition improves immune function in the elderly

TORC1 inhibition enhances immune function and reduces infections in the elderly

Evaluation of of‑label rapamycin use to promote healthspan in 333 adults

About-face on the metabolic side effects of rapamycin

Rapamycin treatment for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: a pilot phase 1 clinical trial

Rapamycin, mTOR & Longevity: What Scienec Really Shows | 091 Matt Kaeberlein, PhD

What is the recommended dosing for rapamycin for longevity?

Targeting the biology of aging with mTOR inhibitors

Effect of rapamycin on aging and age-related diseases—past and future

Rapamycin for longevity: the pros, the cons, and future perspectives

Biohacking Longevity: Personal Stories of Rapamycin’s Anti-Aging Benefits

What is the clinical evidence to support off-label rapamycin therapy in healthy adults?

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rapamycin in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis